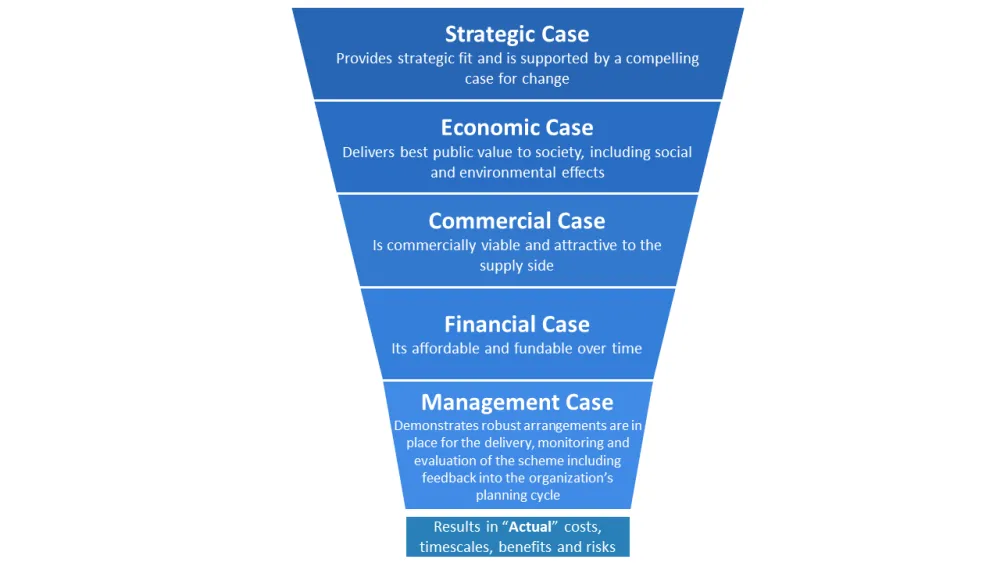

It is for the above reasons that good decisions are based on having sufficient, objective, accurate and timely data and information on programme and project costs, timescales, benefits and risks. As weaknesses in the scrutiny and appropriateness of data and modelling techniques mendaciously distort the information on which investments are approved and mask the business, service and external risks. This is why a business case must never be perceived or used as a medium for simply gaining approval. Better Business Cases™ using the Five Case Model provides decision makers and stakeholders with a proven framework for structured thinking and assurance that the investment proposal:

- Provides strategic fit and is supported by a compelling case for change (Strategic Case)

- Delivers best public value to society, including wider social and environmental effects (Economic Case)

- Is commercially viable and attractive to the supply side (Commercial Case)

- Is affordable and is fundable over time (Financial Case)

- Demonstrates robust arrangements are in place for the delivery, monitoring and evaluation of the scheme, including feedback into the organisation’s strategic planning cycle (Management Case)

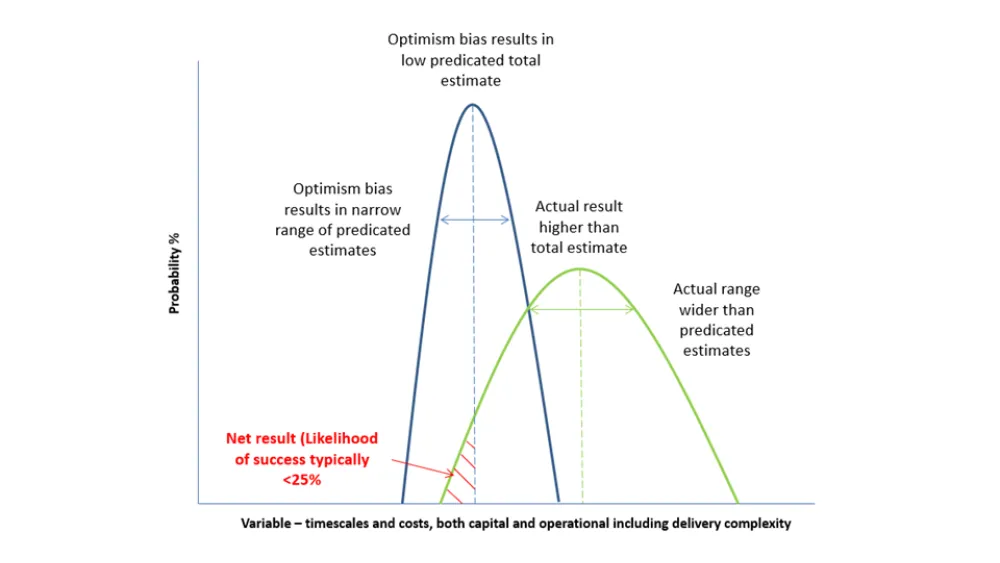

Over-optimism persists where weaknesses in information are ignored and little effort is made across the organisation to benchmark and develop robust estimates or to be honest and transparent about the assumptions made on limited data and information. It's, therefore, critical to organisational performance to start acknowledging that optimism bias exists! One leading entity, Transport for NSW has recognised in their Cost-Benefit Analysis Guide “ways to avoid cognitive bias when developing initiatives is to think in terms of outcomes, exploring a wide range of [viable] options early in development, and avoiding the preferring of an option without the necessary evidence.” A starting point for benchmarking and estimation is to establish a standard unit of measure. The most commonly used measure is a unit of local currency in present day prices (known as “real prices”). Increases in prices due to inflation or other sources of cost escalation should not be included in the values of future benefits and costs.

Additionally, programme and project justification is often predicated on assumptions (typically without evidence) about desirability, feasibility and/or achievability. As such, business cases should distinguish information without any substantiating evidence (assumptions) from that based on probability and empirical data (presumption). As such, explicit adjustments or allowances should be made to the estimates of a project's costs, benefits and duration. These estimates ought to be based on empirical data from past or similar projects, and adjusted for the unique characteristics and complexities of the initiative. This is why forecast benefits stated in business cases (used to justify programme and project viability, achievability and desirability) are better understood if the benefits realisation plan and the business case are approved by the host organisation at the same time.

As optimism is biased to the extent that people expect good outcomes without working to ensure those outcomes occur. Organisations and appraisers alike should acknowledge that optimism bias in business cases exist and seek ways to adjust for it since actual and estimates show the accuracy between prediction and the reality of the programme and project costs, timescales, benefits and risks against complexities in delivery.

Image: Optimism Bias diagram